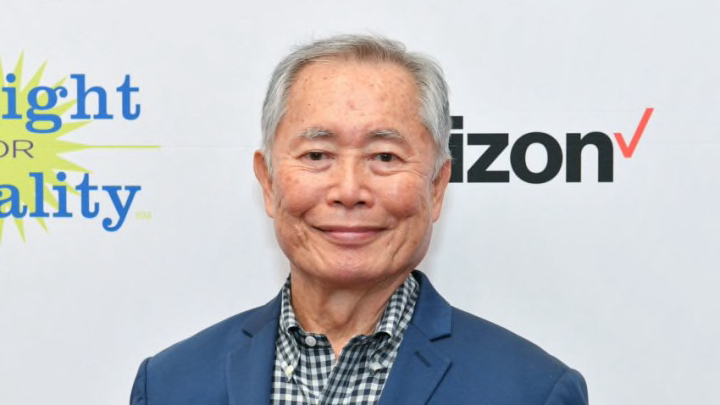

George Takei, who turns 84 on April 20, found fame as Hikaru Sulu in Star Trek. But the work he’s called his “legacy project” is the Broadway musical Allegiance, the film of which became available in a new, single-disc DVD edition earlier this month.

Allegiance is historical fiction set during the U.S. Government’s all too factual relocation and incarceration of nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. From 1942-46, the Takei family was forced to live in the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas and the Tule Lake Segregation Center in California.

The interment exposed the young George Takei to contradictions in the American experience. As he wrote for the New York Times in 2017:

"I remember every school morning reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, my eyes upon the stars and stripes of the flag, but at the same time I could see from the window the barbed wire and the sentry towers where guards kept guns trained on us."

Developed by Takei with composer Jay Kuo and co-book writers Lorenzo Thione and Marc Acito, Allegiance draws from Takei’s personal experiences as well as those of other Japanese Americans to tell the story of the Kimura family.

Uprooted from the farm they own for no reason other than their ethnicity, they are relocated to the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming.

The Kimura family is fictional, but represents tens of thousands of real Japanese Americans forced by their government to grapple with conflicting loyalties to country, kin, and conscience.

George Takei made his Broadway debut in Allegiance

If you’re a Star Trek fan, you owe it to yourself to see Allegiance, even if you don’t consider yourself a musical theater buff.

Not just because George Takei is in it—though there’s no denying it’s a delight to see our “Mr. Sulu” acting, singing, and dancing in his Broadway debut.

Takei brings not one but two roles to life in Allegiance.

For most of the show he plays Kaito Kimura, the family’s elderly ojii-chan (grandfather), whose gardening at Heart Mountain becomes a metaphor for the patient and determined cultivation of hope in difficult times.

And in brief scenes at the musical’s beginning and end, he plays an aged Sam Kimura, bitter veteran of three wars who is, in a different but no less real way, surprised by flowering hope.

Allegiance offers a hard-won message of hope

Star Trek fans should also see Allegiance because, like the franchise we enjoy, this production communicates a message of hope. But it’s a hard-won message, not imagined as an aspiration for the twenty-third century but wrestled from tragic experiences in the twentieth by those who suffered through them.

George Takei has repeatedly said, as he did to The Guardian in 2015:

"We can’t learn from history if we don’t know our history and so many Americans don’t know this chapter of American history. … As a teenager I looked and searched in the civics books, in the history books, there was nothing about the internment of Japanese Americans."

Throughout his life, Takei has devoted great resources and personal energy to making more Americans more aware of the internment. Allegiance is an invitation to engage and reckon with a moment when the U.S. forsook its professed values of “liberty and justice for all” out of fear is powerful and convicting.

Allegiance avoids “preaching,” but does include challenging moments. Given its subject, how could it not?

The traditional “showstopper” dance number in Act I has a boogie-woogie Big Band sound soaked in biting satire of “Uncle Sam, benevolent master.” And its haunting lament for the victims of Hiroshima in Act II, performed in darkness save for footage of a mushroom cloud projected onto the cast’s faces, keep the “Victory Swing” three white GIs sing in the next scene from becoming another Broadway “feel good” song and dance.

But Allegiance relies mostly on winsome characters, humor, and warmth to bring audiences into its story and open them to its message.

Some critics have claimed the show takes too many liberties with history, especially in its characterization of Japanese American resistance during the war. The show and varying reactions to it do make me want to learn more about this chapter in history non-Japanese Americans have for too long overlooked.

Even if the steps Allegiance takes to make more Americans aware of the internment are imperfect or incomplete, they might be an example of “moving a mountain stone by stone,” as Kaito and other characters sing.

Ultimately, Allegiance urges us to believe there’s “still a chance to learn from what has passed,” as one lyric says. Facing the sins and sorrows of the past in order to build a brighter tomorrow is a message and mission all Star Trek fans can support.